Quartet in Autumn by Barbara Pym

A meagre life is still a life

Quartet in Autumn is a story of four small people leading four small lives. They congregate daily in an unspecified office, each edging towards the vague spectre of futility known as retirement. Their worlds are almost satirically meagre, but by casting into the spotlight these humble routines – the barest accounting that makes up a life – Pym's novel expands our empathy rather than narrowing our judgment. There is comic genius in Pym's portraiture but never direct condescension. Her cinematic eye is meticulous, drawing out domestic high drama while maintaining what I can only describe as a British commitment to the propriety of our ageing cast.

Edwin is a widower who has found purpose in extreme church-attending. Letty, the most insightful of the group, is a spinster who lives in a bedsit, with a quiet drive to make life count but completely uncertain as to what that might involve. Mischievous Norman is the spiciest of the lot, but perhaps with the least to offer in terms of introspection. And Marcia – the superbly drawn Marcia – is disappearing by the day, starting with the surgical removal of her breast, and then slowly fading out one cup of sugared tea at a time. Her life, which at times she herself seems startled to be living, is a shrine to frugality, meanness and the vicious protection of privacy. Pym’s creation of this tiny complicated woman, born into a war-torn Britain and driven by a deeply internalised austerity, is a masterclass in believable eccentricity.

This modest ensemble provides a rich portrait of ageing, loneliness and the obscure forms that genuine care can take. Existing as they do outside the acceptable structures of family and marriage, these awkward souls can't quite articulate their intersecting fates. Certainly they are co-workers and even confidantes, but hardly friends. They work together doing a job so generic there is no need to replace them upon retirement. This is London in the 1970s. The world continues to outpace those frozen in another generation.

In the simplicity of her characters’ lives, Pym is able to draw out the theme of simple human connection. Connection doesn't need to mean fireworks. Connection can just mean consideration, even if that consideration is unbearably laboured or explicitly rejected. Consideration can be as simple as treating another human being and their trivial concerns with serious deliberation. It can be as simple as acknowledging that someone takes up space in the world.

This is a book full of the gestures we make towards each other. Over time these gestures can build to a relationship, but oftentimes a gesture remains untethered. We are all constantly hesitating to reach out and jerking away, sometimes with shocking obliviousness. Pym is the record keeper of that which threatens to stay unrecorded. As Letty wonders, “might not the experience of ‘not having’ be regarded as something with its own validity?”

We pity these characters. We fear that we may become them. But we somehow also feel protective of them, perhaps even indignant in defending their value. Their dismal lives, under Pym's microscope, become important, even defiant. The ending of the novel is a generous gesture towards hope, tenderness and the preservation of dignity. The crumbs of community can sometimes be enough to sustain us.

Post Script

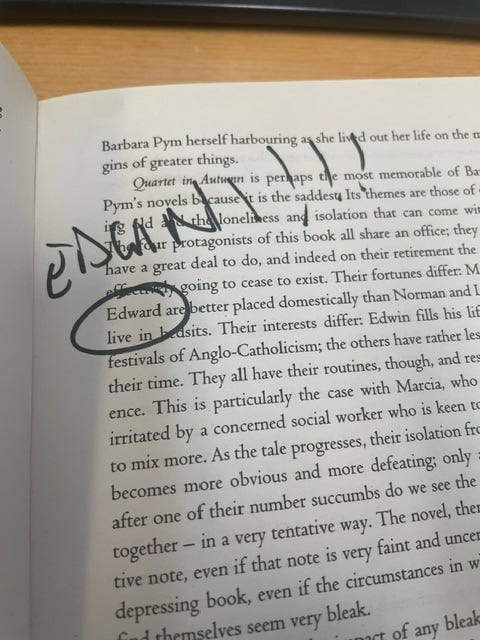

When I was reading the introduction of my library copy of the novel I found an outraged correction as the text had used the character name ‘Edward’ instead of ‘Edwin’ (!!!). I feel this is the exact kind of pedantic commentary the novel sanctifies. It is pleasing to know that Pym continues to be read with a keen eye for any opportunity to express disapproval.