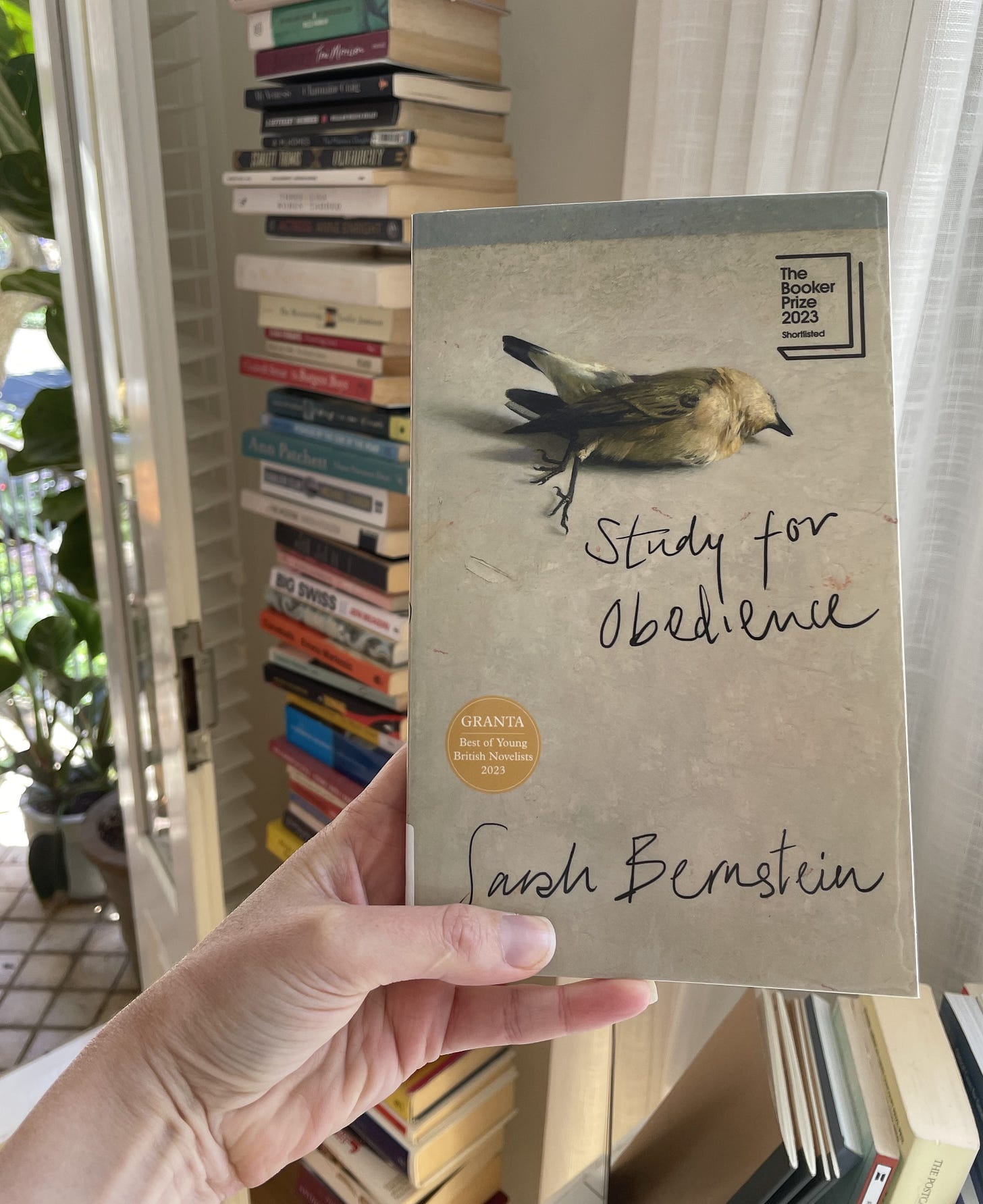

Study for Obedience

Once upon no time

I am not superstitious but I do believe that certain books read in certain times and places are conferred an additional mystical significance. I’ll always remember reading On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan while sitting on the gravelly shores of Weymouth in Dorset County looking out onto the same ragged sea as the characters between my pages. I read Janet Frame’s raw, poetic memoirs (for the first time) under lamplight late into the night as I recovered from a young and impossibly lonely heartbreak. Now I add to this list of literary memories: Sarah Bernstein’s strange and unsettling Study for Obedience, consumed while I was unwell last week, in and out of fever and fatigue, unsure what time of day it was. In sympathy with my disorientation, Bernstein’s book offered a twisted fairy-tale where nothing was as it seemed, or perhaps everything was exactly as it seemed but without clarity as to which was the more sinister proposition.

The narrative set up is simple. A woman comes to live in a nameless northern European village to attend to her older brother who has recently been left by his wife and children. Although set in contemporary times the novel feels frozen in a bygone universe of superstition, subordinate women and subordinate clauses. The voice of Sarah Bernstein’s narrator is anachronistically formal and precise, despite references to remote working, airplanes and mobile phones. Bernstein seems to revel in the discomfort of incongruence, courting the questions suspended in the wake of withholding.

An example of a typical sentence:

When I exited the automatic doors of the airport, the navigation of which had taken me some time since the sensors did not at first register my movement, however exaggerated, so I had to wait until another recently deplaned passenger passed through the doors himself to exit, my brother’s car was already idling at the kerb.

Bernstein’s prose is almost pedantic in its specificity, perhaps reflecting the narrator’s job as a legal transcription typist. Nonetheless the effect of such arcane constructions (‘deplaned passenger’?) is that we are thrown into an uncanny valley where the rules are equal parts unbending and obscure. Furthermore it is as if the narrator’s sentence structures somehow mirror her learned subjugation, and her wariness to be the outright subject of her own life. We learn that she has been brought up to be obedient, subservient, ashamed and invisible – facts that the narrator seems to internalise with no apparent irony. She accepts the townspeople’s intuitive suspicion and hatred of her, and also her brother’s expectations of complete servitude.

The story shifts insidiously, slowly. The more the narrator insists on the reinforcement of the existing power dynamics between her and her brother, between herself and the close-minded villagers, the less sure-footed the reader feels. We forget that we are in a real time and place and move into a medieval fable filled with superstition and ritual. Farm animals die, totems are woven with grass, ancient grudges are upheld. The word antisemitism is never spoken but the allusion hangs thickly in the air. It is a peculiar tale, allegorical and yet profoundly inconclusive, though one can be in no doubt that by the end of the book nothing will ever be the same again.