In an essay called ‘Life and Story’, Sigrid Nunez reflects that ‘writing was an ideal way to escape the world and be part of the world at the same time.’ I think Nunez understands fundamentally that we are all insiders and outsiders. The two identities can sit peaceably or embattled within us, depending on where we are in our lives and the state of the world. This sentiment of duality captures for me so much of why I write, but also why I love to read. These acts give me the strength to be in the world but also the solace of seeing that world contained in crisp linguistic envelopes that can be held and exchanged. The essay goes on to discuss whether it’s important to have a big ‘idea’ before you sit down to write. Nunez concludes that if she had tried to wait for a truly Great idea that was Real and Serious and Original, she would never have been able to write at all. And I find it true that the act of writing itself, at least in Nunez’s work, is the idea. It is the brave thing, to try and say what you mean and work out what you mean all in the same place.

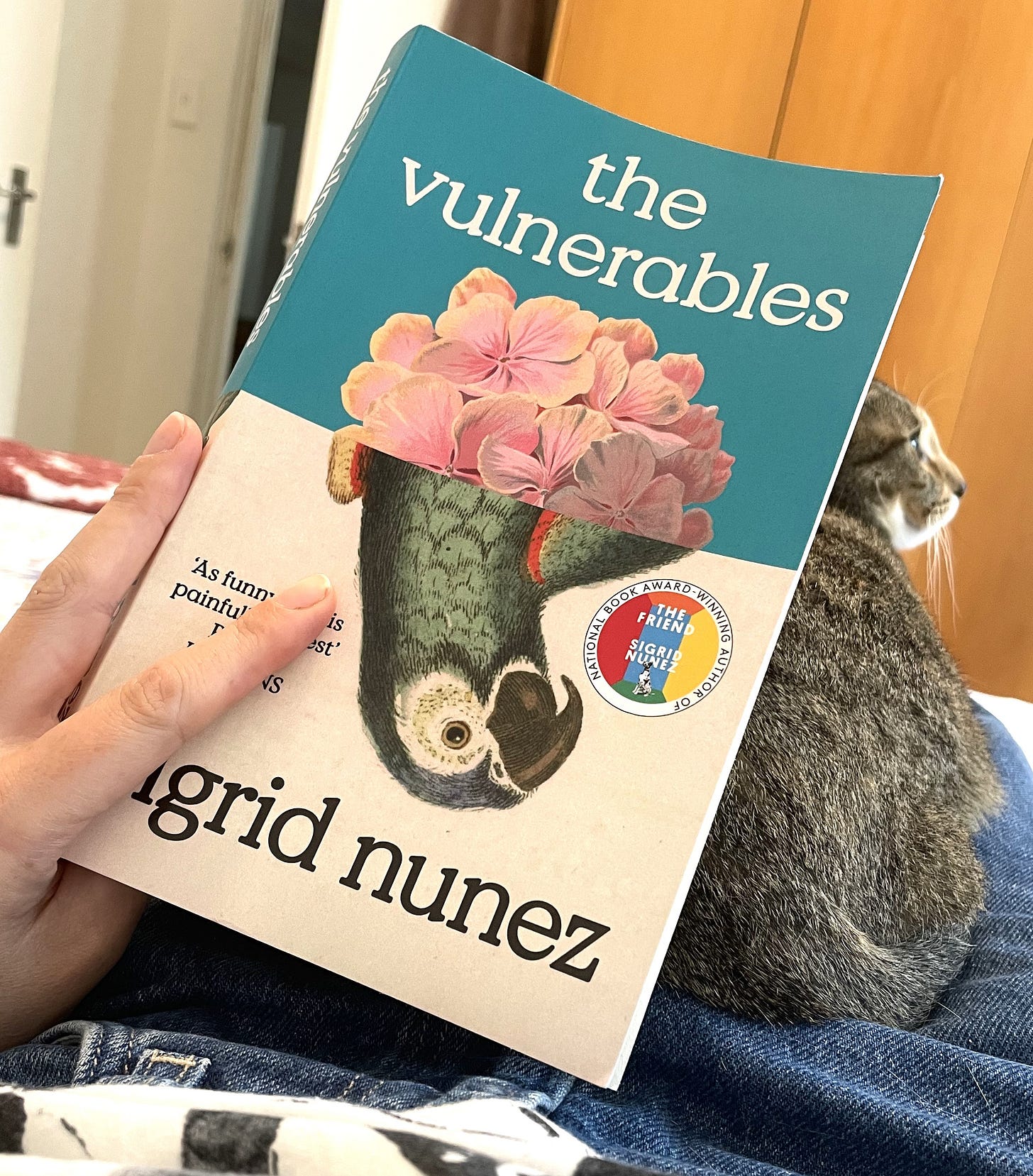

On its back cover The Vulnerables is described as a story about three strangers ‘thrown together’ during the pandemic, but more accurately it is about nothing and everything – purposefully constructed to limit a publisher’s opportunities to summarise events that happen within its pages. It’s about who we are when everything is stripped away, and what it means to write in a time of crisis. Nunez plays with our idea of truth and fiction, memory and imagination, never squaring anything away or colouring within the lines of genre. This description may make it seem like the novel is a postmodern maze of trickery, even drudgery but reading Nunez is smooth and easy. No tricks, just a delightful attempt to say something true.

In the density of its intertextuality, Nunez’s writing reminds me of Deborah Levy’s memoirs. Both writers are in a perpetual conversation with an extensive classical and pop cultural canon of thinkers. In citing all her influences, from Chekhov to Alan Bennett, Nunez makes explicit the irony of writerly solitude. The novel ricochets with a cacophony of quotations and opinions that rattle around in the lockdown of the narrator’s mind. I have heard the phrase ‘a writer’s writer’, but perhaps there is such a thing as a ‘reader’s writer’, as self-evident as that might sound? There is something about Nunez’s work that makes one feel like an insider, like we are all part of a chaotic cacophony of thought and not just witness to it. This is the Nunez magic – as a reader I felt like I had a voice, like I was part of the conversation, absently contributing my own memories and sliding them across the void into the literary mosh pit.

I remember when I was 11-years-old and a boy was infatuated with me. We were in primary school. He was awkward and religious and strange, artistic and with creative talents beyond the scope of my limited imagination at the time. I just saw him as an outsider, and his attentions exposed my fears that I was an outsider too, when I desperately wanted to be inside. He called me at home one afternoon – an extraordinary act of courage in days where one had to face down the risk of talking to a parent to reach their daughter. After a stuttering query about our school debate team, he asked me to go to the year six dance with him. Prepared for the unwelcome invitation I told him I wasn’t really going to go with anyone, or some such evasion. Not a ‘no’ but hardly an encouraging response. Nevertheless on the night in question, he rushed to my side at the one opportunity presented to ‘ask’ a girl to be your dance partner and I had no choice but to accept, resigned to be the reward for his tenacity. I remember the look of pride and relief on his perspiring face. On the last day of school he approached me shyly with a beautifully wrapped package that contained three Ferrero Roche chocolates and a sweet note full of quiet affection. I look back now on the unkindness of my determination to deny any connection between us. In reality, his favour was a clue to my otherness. My fruitless pursuits of more predictable crushes only resulted in small humiliations. I never fit naturally into the popular group at school, and the grief I came to from struggling to belong where I didn’t was the source of so much wretchedness.

The key to this freeform novel lies on its first page, where Nunez reflects that “what matters is what you experience while reading, the states of feeling that the story evokes, the questions that rise to your mind, rather than the fictional events described.” Filled with small observances and memories, The Vulnerables made me think about my past and also my future, as a writer and a human.